A Beesley Lecture delivered by:

David Stewart,

Executive Director,

Markets & Mergers, CMA

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

I’m honoured to contribute to this storied lecture series. I’m a past attendee of many ‘Beesleys’, and one of the nice traditions of the Beesley lectures has been that those who knew and worked with Michael Beesley take a moment to recall him before diving into their lectures. I’ve listened to those accounts over the years. As well as his warmth and collegiality and his loyalty to Birmingham, what shines through was his appetite for debate, fascination with markets and conviction that good economics had a lot to offer policymaking. That this lecture series is going strong into its fourth decade seems a fitting legacy.

My topic tonight is EV charging infrastructure, and the UK’s efforts to secure the investment needed to electrify road transport. It is a case study illustrating how markets can contribute not only to economic growth but to a societal goal like de-carbonisation. All the major themes of competition and consumer policy in 2022 arise: the need for markets to operate alongside government policy; the economics of a consumer necessity, the car, in a cost-of-living crisis; the backdrop of rising energy prices; how to foster innovation; how to deploy infrastructure widely, minimising the risk of enclaves or deserts, whilst preserving competition.

I am speaking this evening in a personal capacity. The views are mine and not necessarily those of the CMA or my colleagues (Endnote 1). That said, I want to acknowledge that almost all the work I’ll discuss was done by others – especially my colleagues in the CMA’s Markets team, led by Daniel Gordon, and the EV charging market study team, directed by Emily Chissell and Sabrina Basran, supported by the CMA’s economists, lawyers and financial analysts. I’m also grateful to many colleagues and practitioners inside and outside the CMA who offered comments or insights as I prepared – a full list is in the published version. (Endnote 2)

My focus is the system in which competition authorities and regulators act to make markets work better. How well do we identify market failures? Are we designing practical and effective solutions to mitigate those problems? How do we make space for other objectives, that aren’t about markets or competition specifically, in a principled and predictable way?

With that in mind, my plan for the next 45 minutes or so is:

- First, to briefly survey the problem: why we are going to need a lot more EV charging infrastructure to meet the Government’s Net Zero ambition.

- Second, to consider the policy framework supporting investment in public charging infrastructure.

- Third, to consider the lessons to be drawn from other sectors or parts of the competition and consumer policy toolkit that might be helpful.

The nature of the problem

EVs are not new but petrol vehicles have long-standing benefits

Electric vehicles are not new. The first electric vehicle was launched in 1884, but petrol vehicles rapidly displaced them.

The advantage of electric over petrol has always been that EVs are quiet and efficient, without emissions at the tailpipe.

The disadvantage of EVs is energy storage: fuel tanks contain far more energy in a much smaller space than any battery yet invented, and pumping petrol is faster than charging a battery. So petrol vehicles have greater range, and refill much more quickly, than EVs.

EVs in climate change policy

The case for EVs – or more accurately, the case against petrol – is grounded in our need to de-carbonise our economy. (Endnote 3)

Everyone here knows the backdrop of the UK’s 2050 net zero commitment. Today, transport constitutes around a quarter (23%) of UK’s CO2 emissions – the biggest single source – almost all of it from road transport, mostly cars (Endnote 4). Coupled with a move to low carbon or carbon free generation, electrification is on the critical path to Net Zero.

To achieve this, the UK is phasing out new petrol vehicle sales from 2030, with hybrids not sold after 2035. Emissions from cars, commercial vehicles and trains are targeted to reduce to a quarter of 2019 levels by 2035 – just under a quarter of the UK’s de-carbonisation commitment. Rapid take-up of electric vehicles isn’t the only element; petrol vehicles will use more biofuels and the Government aims to scrap older, dirtier vehicles more quickly (Endnote 5). There’s also work underway getting people to walk, cycle and scoot more, and drive less.

But EVs are set to take centre stage.

Types of EV charging

The time to charge an EV depends on power output. Overnight charging at home only needs a trickle of power, drawn from the existing grid at off-peak times; charging en route on a long journey in less than half an hour takes very significant power, specialised equipment and often major upgrades to the electricity network.

We can distinguish between private charging (in a driveway or garage, or the workplace), and public charging, where charging is offered to the public.

Home-charging is generally a one-off purchase and installation. It relies on the users’ home energy contract. This works well: most EV buyers with space to do so buy a home charging point. A government scheme (Endnote 6) has helped promote this (Endnote 7). Workplace chargepoints are also growing quickly (Endnote 8).

Public EV charging raises a ‘chicken and egg’ problem: buying an EV is only attractive if you expect public charging to be available where and when you need it. And building EV infrastructure only makes sense if there are lots of EVs on the road to be your customers.

This is not an unusual problem – it often arises in technology markets (getting two groups of users interested in a new digital platform), or in industries like payments, in the business of bringing together buyers and sellers.

In practice, the challenge in EVs is even more complex, since consumers need a mix of charging options – if you buy an EV, you will regret it if you can’t charge at home, or locally, or at work, or you can’t undertake the longest journey your family plans that year. Consumers are acutely aware of this constraint. That’s why the National Infrastructure Commission, for example, concluded this year that ‘the big barrier for expanding EVs ownership and the transition to a net zero transport sector remains the rollout of charging infrastructure’ (Endnote 9).

A critical element in solving this problem for EVs was the government’s decision to set a date for the end of sales of petrol vehicles in 2030. That has had a big impact: awareness of EVs is high and more consumers expect to go electric for their next car than petrol (Endnote 10). Given that impact – and recognising that it carries some risk – it is worth noting that this intervention has very little direct cost. It shapes the market trajectory, effectively firing the starting gun in a race to deploy charging infrastructure in a way that will support that switchover.

Business/operating models

With charging largely outside the scope of retail energy regulation, various business models have been adopted in response (Endnote 11). One EV manufacturer, Tesla, offers its own network for charging almost exclusively for Tesla EVs; other networks can generally be used by any EV. Amongst chargepoint operators, in some cases a full operator funds the infrastructure and sells charging directly to the public; a service provider might provide a chargepoint to a site for a fee, with the site owner then deciding how to offer charging (which might be free, to encourage visits or as a benefit to employees). Some sites operate as concessions – like a full operator but funded through grants – widely used by LAs to achieve rapid roll-out of new sites. Chargepoint operators are typically owned by car manufacturers (Endnote 12), investment funds (Endnote 13), forecourt operators (Endnote 14), or major oil companies (Endnote 15). We have seen new entry and innovation across the value chain.

There is great uncertainty associated with many of these business models. ‘Petrol-like’ consumer expectations – drive up, charge, drive away – are the hardest and most expensive to fulfil. For en-route charging, that model seems inescapable, but for most driving, given time, and provided there are price signals, new consumer behaviours may develop as EVs become prevalent.

Predicted utilisation is sometimes low, especially in areas where the density of EVs remains low. Some operators are betting on forecast increases in usage as EVs become the norm. Some low utilisation installations may help adoption even if they aren’t used very much – people want to know that there is a wide network of chargers before they buy an EV, even if they only ever drive locally. Building these may only occur if they are subsidised.

Scale of the challenge

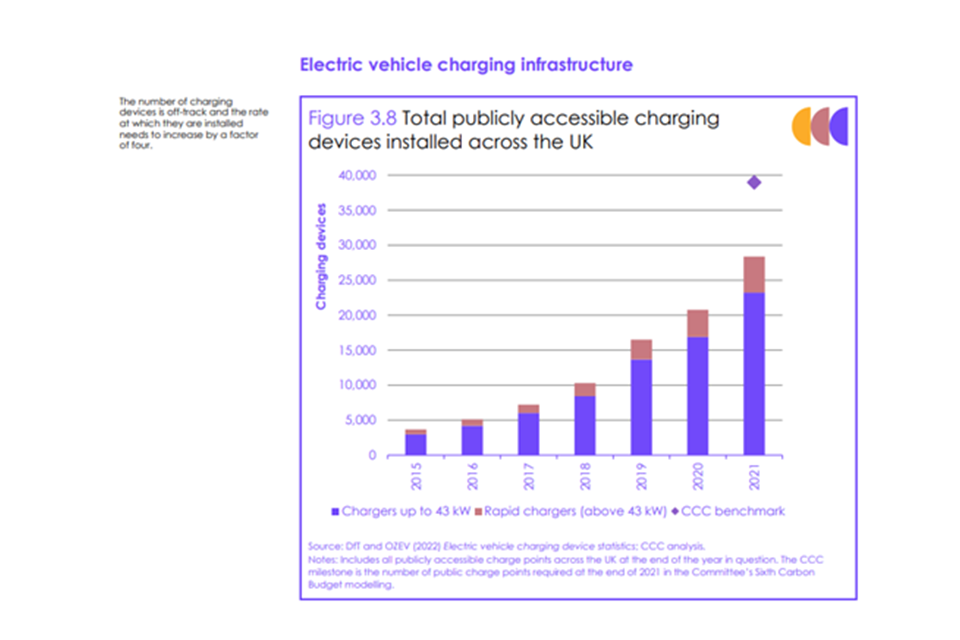

So how are we doing? The Climate Change Committee tracks overall progress towards net zero targets and sets benchmarks for progress on a range of metrics.

Their view was that the UK needed 12 times more public charge points than it had in 2021 to be ready for 2030 – 27k new charge points per year – with especially strong growth needed in mid to high power range charge points, for example 50kW plus (where the number of chargepoints forecast to be needed was more than 40x the number then installed).

In their 2022 assessment, the Committee’s conclusion is that ‘the number of charging devices is off-track and the rate at which they are installed needs to increase by a factor of four’ (Endnote 16).

Here is the shortfall today:

Bar graph showing Total number of publicly accessible charging devices in the UK, it starts at below 5,000 in 2015 and gradually increases to almost 30,000 in 2021

And here, more starkly, is the NIC’s view on the overall trajectory, using the same data (Endnote 17).

Bar chart showing the required number of charge points needed by 2030 (around 300,000 to 475,000). The chart shows that between 2015 and 2021 the number of chargers available has not reached 50,000

The investment challenge

To build infrastructure on this scale demands significant investment – probably at least five to ten billion pounds for the chargepoint networks (Endnote 18), and a material amount in the electricity network. We already see significant private investment, and competition between chargepoint operators. But levels of investment will need to increase markedly as EVs grow.

If chargepoints don’t grow in line with EVs on the road, then drivers may face capacity issues – that is, queues or delays (Endnote 19). As well as capacity, there is also coverage to consider: there is a risk of duplication in some areas, and lack of service in others – as has occurred with ATM deployment, for example.

To attract investment, public chargepoints need to be profitable – they will only recoup investment when they are used at a price that covers their costs. For public charging, this is risky early on, when EVs are less well-established and consumer charging practices are still developing. Demand uncertainty affects the type of private sector investment attracted to the sector (deterring investors seeking long-term low risk infrastructure investments).

Early private investment in charging was focused where demand, and hence returns, are strongest – home and workplace charging. Investment has been weaker on en route and on-street charging, where business models are more complex and risky. Worst of all is public charging in remote areas, where some deployments may never be profitable without subsidy. But these are precisely the types of charging that reduce consumer barriers to take-up.

Impacts of EVs on the electricity network

Increased demand

EVs increase demand for electricity, and require greater capacity, often in new or unusual places (for example, alongside motorways). Demand is expected to increase by around 20-30%, with transport accounting for around a fifth of all electricity demand (up from virtually none today) (Endnote 20).

Electricity network operators are therefore critical players in EV adoption. If public charging is the norm, local networks (DNOs) need to upgrade connections and strengthen the network. National Grid needs to ensure that the transmission infrastructure can meet these new demands.

Connectivity

When charging was first launched, the cost of upgrading the electricity network was carried in the business cases for new chargepoints. That lead to high incremental costs and in some cases, very lumpy outcomes, as capacity is exhausted. Ofgem has since taken steps to spread these costs over a wider set of customers.

Separate from costs, delays in securing network connections have also been a concern. Operators have argued that a more transparent and timely process would significantly help the faster roll-out of chargepoints at scale. This is linked to wider problems with network pricing, including the lack of locational pricing – although that might help in some ways and make other concerns, such as access in remote areas, even harder.

Smart charging

On the other hand, EVs also provide a new way to make the electricity grid more efficient.

Smart charging – that is, the use of home and work charging points that are linked and able to be coordinated – enables better use of network assets by shifting demand away from peak periods, and by charging when the wind is blowing, and the sun is shining. Electricity can also flow out, with EVs exporting stored electricity during periods of high demand or low electricity supply.

Early trials seem quite positive, and Ofgem has made this a priority, recognising the potential to achieve substantial shifts in peak EV demand. These benefits are a potential externality arising from EV adoption – only some of these benefits can easily be captured through market signals (such as time of use tariffs) in slower EV charging which provides them. More generally, they are also likely to work best only if there is a successful shift to a smart energy network more generally, with half-hourly charging providing incentives on network operators and energy suppliers to offer tariffs to consumers that reward shifts in consumption away from peak times.

Taking stock

So, to recap: early take-up of EVs and deployment of charging infrastructure has proceeded rapidly. Consumers are largely on board. We are starting to see the sort of growth associated with other mass-market adoptions of consumer technology.

But the glass is half-empty: the UK is off-track in terms of meeting the Net Zero target. To achieve it, the UK needs to quadruple the pace at which new public chargepoints are installed. For that, major new investment will be needed in chargepoints, as well as a significant upgrade to the electricity network.

Policy framework supporting EV charging infrastructure

This need for investment creates a public policy challenge. The environment facing investors is complex, encompassing many different public bodies. First, central Government (for fiscal support and the net zero target itself). Next, the devolved administrations, especially in relation to devolved powers such as transport policy and planning. Finally, local authorities for local planning decisions and permits for streetworks, as well as each being a major site provider. And there are a slew of statutory agencies to consider, including Ofgem and URGENI, OZEV and so on.

UK government strategy

It is therefore welcome that in March this year, the UK government published Taking charge: the electric vehicle infrastructure strategy that aims to ensure that charging infrastructure is not a barrier to the adoption of electric vehicles (Endnote 21). Having a clear and ambitious national strategy set by central Government was the first recommendation of the CMA’s market study.

The strategy recognises that today’s roll-out is too slow. Public charging has not always been as reliable or fast as consumers have a right to expect. The business case for deployment of new chargepoints is hard in areas of low utilisation or where connection costs are high. Getting those connections from the energy network operators can be slow and expensive. And finally, that there is a need for local engagement, leadership and planning.

In response, the government focuses on two interventions: one, to accelerate the roll-out of high-powered chargers on the strategic road network through the Government’s £950m Rapid Charging Fund, and second, to transform on-street charging by setting an obligation on local authorities to develop and implement local charging strategies in their areas.

Equally importantly, the strategy winds down existing subsidies that are no longer needed, for example, for home chargepoints.

Finally, the strategy rightly focuses on the consumer experience. It sets a clear direction in favour of open data, price transparency, widely-accepted payment methods and reliability.

There are risks to consumers from government direction-setting. These can be partly mitigated by leaving space for experimentation and differentiation about how to execute the strategy. But clearly, if we have an important national priority to decarbonise transport, then it is a good idea for both private and public actors if there is a clear strategy about how to do so.

To execute this strategy there is a complex set of interventions which I’m not even going to attempt to survey exhaustively. But in keeping with my focus on our competition and consumer framework, I want to draw out a few points.

EV policy builds on established principles

First, the approach to EV charging reflects our competition and consumer policy framework generally. The approach varies by the scope for competition:

Charging infrastructure is generally competitive. Markets will drive investment. The CMA can help promote competition using the tools that promote and protect competition across the whole economy. Specific rules will be set to deal with specific problems.

The electricity network supporting charging is a monopoly. Investment will be broadly governed by regulation. Ofgem sets rules designed to mimic the constraint that competition would otherwise provide.

Separating out and regulating monopoly elements to enable competition elsewhere is a foundational element of UK competition policy, visible in virtually every sector-specific regime, from major airports, telecoms, or as in this case, energy networks.

This approach ensures that the monopoly energy network cannot foreclose competition in chargepoints. But it creates a new challenge: to coordinate investment between them.

Policy can vary in different parts of the UK

Second, the approach supports variation between different nations of the UK.

In England, the model is primarily private sector investment in public charging (with a more mixed picture for on-street charging). This requires less public investment, and the risks associated with investments being taken by private investors. There is scope for innovation in business models and approaches. As stable and mature business models emerge, over time, provided the market is competitive, prices are likely to align with costs, offering services at efficient levels.

In Scotland, the Scottish government operates a network of public charging points via ChargePlace Scotland, which contracts with site providers (hosts) that have chargepoints in that network located on their property. That requires some public funds to invest, and willingness to take the risks involved in doing so. It brings different trade-offs: government can coordinate deployment (for example, ensuring the number of chargers installed meets the target) and align with other services (like public transport or local government), especially important for on-street deployment. One major difference was that, initially, charging in Scotland was free. This encourages take-up of EVs, but potentially crowds out private investment and creates expectations by consumers that may not be sustained if the policy changes. With its latest strategy, Scotland’s approach is now transitioning to a greater role for private sector investment (Endnote 22).

Choices between public or private ownership are political questions, and answered differently in different circumstances. Where there is scope for competition, whether it involves public or private undertakings or both, the CMA can have a role in making those markets work well for consumers. The CMA has made Net Zero a strategic priority and is already active in the sector, so we might expect it to remain vigilant (Endnote 23).

Local government action is critical

Third, it is clear that local government is in the lead in deciding its own strategy for EV charging, supported by money and resources from central government (Endnote 24). This is particularly important for on-street parking, and hence, for urban areas where fewer drivers have room for private off-street charging.

Regulating the electricity network to support decarbonisation

Fourth, I want to touch on the central role played by the energy regulators.

Ofgem, which regulates electricity in Great Britain (but not Northern Ireland) set out its own strategy to support EVs in 2021 – here’s the six outcomes and four priorities for its work, as well as the steps needed to deliver those outcomes. (Endnote 25)

“Source and further details: Enabling the transition to electric vehicles: the regulator’s priorities for a green fair future.

I don’t plan to discuss these in detail, but a few points bear emphasising.

Ofgem addresses some problems that look a lot like conventional utility regulation.

For example, energy networks need to respond to requests for new connections and enhanced capacity where it is needed. Some of this involves conventional network planning. But some of it does not. We’ve already seen that demand for EV charging is uncertain, both in terms of types of charging, and the places where that demand will be needed.

Ofgem regulates energy networks via five-yearly rolling incentive-based price controls (Endnote 26). This type of regulation works best when demand is predictable, ideally with robust forecasting against which ‘efficiency’ gains can be offered.

This model has an Achilles heel: how do you bring customers’ interests to the table? Different sectors have grappled with this challenge: sometimes, wholesalers or major players – or in some sectors, insurers – can act as proxies; sometimes, companies are pushed to internalise customers’ needs through engagement or a ‘social purpose’. The most successful solution is not to solve the problem at all, but to remove regulation as technology enables competition deeper in the network (Endnote 27).

In energy, that type of de-regulatory step-back has not generally been possible. And as we all know, energy policy is not confined to the regulatory sphere, as the geopolitics and social impact of the current energy crisis illustrate clearly.

No organisation has done more than Ofgem to find innovative ways to adapt incentive-based regulation to enable network transformation, despite these headwinds. They deserve credit for the development of the 2013 RIIO model and its successors, that bring innovation and incentives literally into the equation whilst maintaining the underlying regulatory elegance – there is no other word for it – of the RPI-X model.

Ofgem’s challenge is that the boundaries of the network are shifting in different directions and in unpredictable ways.

On the one hand, new smaller infrastructure elements are proliferating – new charging infrastructure but also small-scale generation (including renewables at an industrial and domestic level). Adding new network connections has become more important. To support EV charging, Ofgem shifted the recovery of costs of new network connections to a wider set of customers (Endnote 28). This lowered the direct cost of new infrastructure deployment but, given the absence of time-of-use and location-based pricing, arguably reduced the granularity of price signals.

But it isn’t just about cost: the reliability and timeliness of delivering new connections is vital for new site deployment. This has been a perennial problem in other sectors – Ofcom spent many years regulating service charges to improve reliability in delivery of network connections, notwithstanding functional separation designed to eliminate the problem at its source. Spoiler alert: the problem is still with us, twenty years on.

On the other hand, Ofgem is grappling with the conceptually opposite challenge: how to regulate in a way that makes the whole of the system work together in a cohesive way, to deliver the top-level transformation that is required and to enable the systems necessary to support outcomes like smart charging.

Ofgem’s strategy in this respect is still under construction – but what is clear is that there is a trade-off between the degree of uncertainty as to future conditions, and the precision and effectiveness of incentive-based regulation. A certain degree of uncertainty can be taken into account in the modelling process, and, to an extent, built into the charge control design.

But beyond this point, the financial performance of regulated monopolies is exposed to highly uncertain changes in consumer technology and behaviour. This is difficult for investors in infrastructure, generally looking for safe and stable returns. In principle this is bad both for investors and for the public, because there are risks in both directions. There’s a more practical problem, too: both at the start of the charge control, and during the life of the charge control, companies have better information and multiple opportunities to tilt the balance of probabilities in their favour, meaning that the most common way these systems go wrong is to over-reward investors at the expense of consumers, through returns exceeding the cost of capital and through overinvestment.

I think it is reasonable to conclude that we are approaching the limits of what can be done with the current model, in the current climate. In Ofgem’s call for inputs in relation to the distribution network architecture in April this year, and again in their open letter to the sector just a few weeks ago, Ofgem is signalling its desire to refocus the regulatory system so that there is a greater degree of accountability for some of network activities that can be unbundled from the role of day-to-day network operation. This is worth exploring, but it means more complex structures, with further vertical relationships as a focal point for regulation. It is also happening at the same time as other big changes in the system, such as the move to half-hourly settlement, and the electrification of heating and industry (Endnote 29).

The truth is we do not yet have a regulatory model that works well for monopolies undergoing widespread changes that demand a coordinated response. By far the most successful strategy to escape this problem has been to open up markets to competition where we can – think of the benefits to consumers in markets like telecoms or civil aviation (although noting that aviation faces its own decarbonisation challenge).

The point for tonight’s purposes is this: investment in EV charging infrastructure is at least partially exposed to the regulatory risk associated with the wider energy market, entangling it in one of the most complex, and most important, policy challenges we face.

Consumer policy has a vital role to play

Finally, consumer policy also plays a vital role in EV charging. The UK government has been active in responding to specific issues relating to charging infrastructure that, left unchallenged, could undermine the successful take-up of EVs (Endnote 30).

New rules require that payment methods are not brand-specific, and can be accessed without a smartphone or pre-existing contract with the driver – so charging can happen even in mobile not-spots. Charging needs to be accessible to all – reducing barriers to disabled and older consumers enjoying the benefits of an EV (Endnote 31).

Open APIs for chargepoint location and availability data is also mandated. Just as Open Banking (established by the CMA in relation to account information) underpins a wave of fintech innovation, a norm of open data in charging lays a foundation for future innovation.

Consumer rules always bring costs as well as benefits. Too many rules can restrict innovation and market flexibility. Detailed consumer rules in fast-moving areas like payment systems are particularly at risk of being overtaken by events. And there is scope for regulatory creep.

But these rules seem to me to be aiming for a reasonable target: to nudge an emerging market into a competitive and open equilibrium, at a time when conditions may create a harmful path-dependency if left to the market alone. The aim is not regulation for ever, but to avoid unwanted lock-in and confusion becoming the norm early on, to make charging an electric vehicle as simple as paying for petrol. And that lays foundations for digital integration with a smarter energy grid and for wholly new developments such as autonomous vehicles or commercial models for transport that do not depend on vehicle ownership.

Headwinds

So far, so good. But there are some cautionary notes to consider.

EV infrastructure investments face substantial policy complexity

Notwithstanding the government’s strategy, a challenge facing investors is the sheer complexity, and relatedly, regulatory risk.

As an example: the CCC’s 2022 recommendations to Government identify four different central government departments and all three devolved administrations. Local authorities also have a critical role to play. That’s before one includes the role of Ofgem (named as a key actor) or the CMA (not even appearing).

All of these recommendations make sense on their own terms. But taken together, they illustrate the degree of regulatory risk for these projects. That risk is straightforwardly priced into the cost of capital and creates the risk of stranded assets when policies change.

Mixed incentives

A second challenge is that different actors have different incentives, and so there will be opportunities for derailment or diversion.

Experience in other sectors suggests that the more complex a regulatory system is, the more scope there is for logjams or strategic delays. We should not be naïve that all segments of the market will welcome the arrival of EVs. There are business models and investments based on the existing petrol supply chain and consumer habits.

‘Black swans’

A final challenge: many external factors affecting take-up of EVs are outside the control of the UK policymakers.

The current inflationary and energy crunch facing consumers is one of them. Global manufacturing supply chains are another – right now, a tight international semiconductor market means that there is a significant waiting list to get a newly-ordered electric vehicle. Potential bottlenecks in rare earth metals needed for EV battery production, or competition for key resources from other industries, are all sources of risk, especially in a world where the likelihood of uncontrollable and unforeseen weather events seems to be rising.

Options for EV charging infrastructure from other sectors

So against that policy backdrop – what might the competition policy toolkit drawn from other sectors or other countries offer us in relation to EV charging?

Subsidies will remain part of government’s toolkit

One option, which I’m not going to discuss in detail, is greater subsidies to accelerate progress. Subsidies are likely to remain important. I’ve already mentioned some externalities and other factors that mean they may be needed to get efficient outcomes in this sector. Experience shows that well-designed and targeted subsidies can co-exist with, or promote, vigorous competition (Endnote 32).

Government takes decisions to grant subsidies, not the CMA, although we have specific role in providing advice to public authorities on more complex and distortive subsidies as part of the new domestic subsidy control regime (Endnote 33).

So what other options might we have?

Regulate outcomes directly

We could regulate outcomes directly – specifying where infrastructure should be built. This type of intervention is likely to be important if the market underinvests in more remote areas. Universal service schemes can require a sector to cross-subsidise or spread costs of infrastructure deployment across customers generally. The benefit is a guarantee that infrastructure is built everywhere we need it, where private investment without such a scheme will tend to cluster in profitable areas first and others, later or not at all. Often this involves ‘competition for the market’, in a tender or auction.

Many different approaches have been adopted, including USOs, regional franchises, and so on. As well as national schemes, it’s possible to imagine more locally-focused schemes, with a local authority or a regional group of them packages up sites into groups to ensure coverage, with the licensee internalising the cross-subsidy. A variation on the theme would be requiring charging to be offered to particular groups – key workers for example – on preferable terms or for free, just like a commercial developer building social housing to avoid creating enclaves.

Ensure a competitive market structure

In some sectors, regulation imposes a competitive market structure. This was done, for example, when the UK government’ decided to sell 3G spectrum to five licensees.

The main drawback is that you have to know – or accept you will determine – the model of competition. In the case of EV charging, for example: should competition be between multiple providers at a single motorway services site, or should there be primarily competition between sites, with each having a single provider? Currently these questions are left to be resolved through market processes and the application of competition law (Endnote 34). But if things went in a different direction, it is possible to imagine a more intrusive approach establishing, say, four major players across the MSA network, each with a critical mass of sites (or present at every site).

We may also have to consider market structure through merger control. Shiny new industries often have lots of entry, followed by consolidation. Could a national monopolist in charging infrastructure emerge, akin to the UK cable industry, which moved from regional franchises to a single national network through a series of largely vertical mergers? (Endnote 35) If locally or regionally dominant players emerge, this seems quite plausible. Should we prevent that occurring? If so, what tool would we use – sector regulation or a market-based intervention to consider divestment? At this distance, we can only speculate.

These are high-stakes but also high-risk interventions. The lesson from other sectors is that if we can avoid getting into setting the terms of competition, we should. But if, for example, there was a failure of a competitive market to emerge for en route charging, interest in these sorts of interventions might grow.

A clearing house to resolve issues quickly

If conflicting stakeholder interests create incentives for strategic delay, we could establish a way to resolve disputes quickly. This matters in sectors where there is an incumbent with turf to defend, but it can also be useful to overcome the political economy of new infrastructure, where the winners are future consumers and the losers are today’s vested interests. This might include a public body that is empowered to act quickly, with binding decisions issued on a fixed timetable, as happens in telecoms or construction.

A variation on this theme is appointing an individual to act as a facilitator, to bring together players and drive forward a ‘whole of industry’ approach to resolve technical or operational issues. This has worked elsewhere precisely because such an individual is not a regulator – they do not, for example, operate with the same framework of administrative law duties and written decisions. This was used to good effect in relation to local loop unbundling in telecoms, and in competition law, we have seen purpose-built bodies like the Groceries Code Adjudicator. In mergers, there is a long history of appointing monitoring trustees, albeit in a more limited role.

This would be relevant where problems are operational, not theoretical, and a good enough answer that keeps things going is better than a drawn-out process to precisely the right one. Industrialising the process of deploying upgraded connections might be a candidate.

Systems or asset sharing

We could facilitate – or even to require – charging operators to share assets or infrastructure between competing networks. In mobile, this has enabled greater efficiency in site-planning and reduced environmental impact, whilst preserving competition.

Competition law provides the framework for companies to quarantine shared activities from their competitive businesses, including to secure environmental benefits where those benefits are passed on to consumers (Endnote 36). Regulated infrastructure sharing has a more chequered history – there are rules today that in principle offer far-reaching scope for cross-sector sharing of infrastructure, but in practice, as far as I am aware, they have never been used. But street furniture or other assets might usefully be considered as candidates for a fast and effective access regime to speed up roll out and reduce costs.

Summing up

I will stop there – because four examples is enough, I hope, to make my point that we have a nuanced and creative toolkit that can be used to reduce barriers to market entry, unblock issues and open up markets to more effective competition.

With each of these tools, there is a regulatory Faustian bargain: we can address the market failure in front of us, helping consumers – but at the cost of a fresh risk: regulatory failure.

With that trade-off in mind, there’s a couple of ‘no regrets’ steps to add to the list.

Joined-up regulation to reduce regulatory risk

We should do everything we can to make policymaking more transparent and predictable. One way of doing that is to ensure public bodies talk to each other and align sensibly.

In Open Banking, for example, the CMA joins with the FCA and PSR and Treasury to form a joint regulatory committee, bringing all the relevant agencies around the table. In digital regulation, a four-agency group (the DCRF) enables dialogue across bodies dealing with competition, digital policy, financial services, communications and data protection. The UKRN (the group of economic regulators) recently worked together to produce principles governing the setting of cost of capital. In different ways, each of these structures helps reduce the risk that regulators will head in different directions.

In relation to EV charging, we already have OZEV, which aims to bring together the different parts of the UK Government (Transport and BEIS). But if the aim was to accelerate infrastructure delivery, then ensuring greater alignment between public bodies involved in EV charging infrastructure might be useful, and could reduce the regulatory risk and hence financing cost to the sector.

Making the regulatory system fair and focused

We should also do all we can to strengthen the basic building blocks of our competition policy regime.

That means attending to the basics of best practice:

- Rights of consultation and defence should be clear, and regulators should observe them scrupulously, approaching every issue with an open mind.

- Decisions need to be driven by evidence alone, using reliable economic frameworks. This does not mean limiting ourselves to orthodoxy – we need theories of harm that reflect the dynamism and complexity of markets we analyse. But we need to be always ready to explain how and why a new approach makes sense.

- We should be focused on interventions that are proportionate;

- Rights of appeal should be effective and prompt, offering the opportunity to fix regulatory mistakes when they occur; and

- Agencies should be constantly learning from past decisions – good and bad. There is no better way to improve our chance of taking good decisions today than looking at previous decisions that we thought would be good – but turned out badly.

- Above all, it means protecting the central pillar of the UK regime: the independence of regulators. That independence, and the predictability it implies, underpins the assessment of regulatory risk in any business case and contributes directly to the investability of UK infrastructure.

Concluding point

I said earlier that the consensus on EV charging infrastructure is that the glass was half-empty: we aren’t moving fast enough to meet our target. That’s true. But the point of the metaphor is that the glass is always also half-full. That’s the point I want to finish on.

We promote competition, and regulate monopolies, not as ends in themselves, but to improve the lives of our fellow citizens, by making markets – and our economy – fair, open, and productive, helping to generate wealth and encouraging innovation.

But well-functioning markets can contribute to more specific goals, too, such as the UK’s Net Zero commitment.

It is often said that the UK’s system of economic regulation is ‘world class’. We rarely articulate precisely what that means. The defining characteristic of the UK competition and consumer regime is its specificity. Each intervention responds to a real-life problem, and rests on a specific case for action or theory of harm, tested against the evidence. Thus we ‘pick important problems and fix them’ – we practice the regulatory craft (Endnote 37).

Over time, that simple technique can lead to complex structures. As we have seen in relation to EV charging infrastructure, there is a lot of activity: central government strategy, national and local authorities and a range of public bodies including the CMA.

It takes good institutional design to avoid different objectives becoming entangled. We should always look for ways to make it simpler to navigate – dealing with multiple agencies raises costs and risks. But as long as they are focused and committed to working together efficiently, having clear functions and roles allows each agency to do specific tasks well, and be held accountable for the time, money and people they use. In my experience, that degree of focus is correlated with their success. Regulators with blurred responsibilities and who are asked to internalise major social trade-offs can find themselves struggling to reconcile their objectives or having to fudge or dodge big questions.

The UK is not alone in looking to restore growth and prosperity in difficult times while also meeting the challenge of climate change. But just as during Michael Beesley’s time, the UK is looking to the potential of competitive markets to drive progress and secure the investment and innovation we need. Not every use of competitive markets automatically succeeds, and we should be ready to acknowledge the limits of markets. But when markets work well, the results can be not just the prize we anticipated, but, often, possibilities that we couldn’t have imagined when we began.

The UK’s enduring contribution to that work has been to think deeply about how competition policy can help secure these benefits for consumers, and how to design independent and effective public institutions to support that.

By setting a stable and reliable framework, the UK maximises the chances that we can accelerate the pace of change and hit or beat the 2050 target. We don’t yet know whether we will achieve that. But you can see the shape of the curve we’re on: the mass market shift to electric vehicles is underway, and it is happening quickly.

And because we are adopting a model that promotes competition – and the benefits of innovation, resilience and adaptability that come with it – EV adoption is more likely to produce new jobs, open up new industries and offer opportunities to try new technologies and business models.

As always, the credit for that success belongs to the people working in that new industry: not just engineers and entrepreneurs, but all involved, from construction workers to cleaners, who will do the hard work of effecting change.

But a truly world-class – that is, well-designed, focused and accountable – system of competition and consumer policy can be a critical enabler of that success. By providing clear and robust regulatory rules, by pushing markets towards competitive outcomes by challenging anti-competitive conduct or unfair practices, and by ensuring the market structures remain contestable by challenging anti-competitive mergers, the CMA and the other UK economic regulators can play a vital role in delivering the greener future that millions of our citizens demand.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: These comments are not intended to reflect on any current or anticipated CMA proceeding.

Endnote 2: This paper is based entirely on information in the public domain. I am grateful to the following people for useful discussions or insights: Paul Brisby, Emily Chissell, Adam Cooper, Graeme Cooper, Michele Davis, Richard Feasey, Daniel Gordon, Stuart Hudson, Gavin Knott, Jason Mann, Stuart McIntosh, James McKemey, Rachel Merelie, Joe Perkins, Deirdre Trapp, and Mike Walker. All views and errors are mine.

Endnote 3: Although there are other benefits from electrification – for example, one eighth (12%) of NOX emissions in the UK are from cars.

Endnote 4: 91% of transport emissions are road transport. CCC 2022 Report to Parliament, figure 3.1 page 117.

Endnote 5: Hydrogen might be the green fuel for larger vehicles, including some trains.

Endnote 6: Earlier, the EVHS – on 1 April 2022 the EVHS was replaced by a new scheme, the [EV chargepoint grant(https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ev-chargepoint-grant-for-flat-owner-occupiers-and-people-living-in-rented-properties-customer-guidance#new-guidance-from-4-august-2022).

Endnote 7: The OZEV forecast that by 2025, 5% of UK homes with eligible off-street parking would have a grant under the EVHS. The government’s strategy is now to wind down subsidies for home charging.

Endnote 8: The CMA recorded that there were 13,000 such chargepoints installed by mid-2021; in the year since then, that number has doubled, with one researcher projecting 1.4m by 2030. CMA MS para 3.13; OZEV Common misconceptions about electric vehicles leaflet, April 2022 (‘Government has supported the installation of over 26,000 workplace charging sockets as of April 2022’). 1.4m forecast was made by Delta-EE, cited by CMA MS para 3.13 footnote 48.

Endnote 9: Charge point access remains key to expanding EV rollout – NIC

Endnote 10: Department for Transport (2021), Technology Tracker: Wave 8 p.5

Endnote 11: For a discussion of the commercial/operating models for EV charging and how the retail energy regulatory rules apply (or do not apply), see Ofgem, Taking charge: selling electricity to electric vehicle drivers.

Endnote 12: For example, Ionity

Endnote 13: For example, Instavolt, Gridserve

Endnote 14: For example, MFG

Endnote 15: For example, Shell, BP

Endnote 16: Source: 2022 Progress Report to Parliament

Endnote 17: Source: Infrastructure Progress Review 2022

Endnote 18: The CMA considered that implied UK-wide investment in chargepoints needed of around three to five billion pounds but with numbers in the six to ten billion pound range easily generated using slightly tougher forecasts.

Endnote 19: The CMA MS noted that in 2019, there was one charge point for every six EVs. Availability might have been limited but capacity per user on the network was relatively high. By 2020, that looked more like 1 to 10; by 2021, 1 to 21.

Endnote 20: There are a wide range of estimates of the long-term demand impact of EVs for electricity. A key unknown is the question of how much smart charging can reduce peak load.

Endnote 21: Taking charge: the electric vehicle infrastructure strategy

Endnote 22: A network fit for the future draft vision for Scotland’s public electric vehicle charging network

Endnote 23: See the CMA’s November 2021 decision to accept commitments modifying Gridserve’s long -term contracts for motorway charging that granted exclusive rights over major sites for very long periods. The commitments limited the exclusivity of agreements between Gridserve and the three MSAs to five years (through to November 2026), and to carve out from that exclusivity any deployment of chargepoints that uses new capacity brought online as a result of the Rapid Charging Fund. The outcome strikes a balance, enabling a planned £200m tranche of investment by Gridserve to proceed, but opening up scope for competition earlier than would have been the case.

Endnote 24: See, for example, the recent decisions about the Local EV Infrastructure (LEVI) funding.

Endnote 25: Source: Enabling the transition to electric vehicles: the regulator’s priorities for a green fair future

Endnote 26: From 29 Sept Ofgem open letter: ‘Since 2013, we have used a framework to set the price control across each gas and electricity network called RIIO (Revenue = Incentives + Innovation + Outputs). Most recently, the RIIO-2 price controls for electricity and gas transmission and gas distribution companies commenced on 1st April 2021 and will run until March 2026. 4 The next price control for electricity distribution companies (RIIO-ED2) is currently being finalised and will cover the five-year period from April 2023 to March 2028.’

Endnote 27: See, for example, Ofcom, Strategic Review of Digital Communications

Endnote 28: (SCR)

Endnote 29: Ofgem Market wide half-hourly settlement decision

Endnote 30: Government response to 2021 consultation on consumer experience at public chargepoints

Endnote 31: RIDC, Inaccessible charging a barrier to disabled and older drivers

Endnote 32: For example, the CMA’s recommendation in the 2021 market study was that RCF money is contingent on having multiple CPOs at each MSA.

Endnote 33: Following Brexit, the UK has established the Subsidy Advice Unit (SAU), a new CMA function created by the Subsidy Control Act 2022 (the ‘Act’). The SAU assists public authorities in awarding subsidies that comply with the requirements of the Act, by providing independent non-binding advisory reports regarding certain subsidies that are referred by public authorities, taking into account any effects of the proposed subsidy or scheme on competition or investment within the UK. For more information, see the CMA’s recently published proposed guidance on the new regime.

Endnote 34: In the MS, the CMA saw limited competition between MSA sites, and expressed the view that it thought multiple operators on one site was more likely to be the competitive outcome. In the Gridserve matter, the CMA specifically rejected arguments that competition between sites would be sufficient.

Endnote 35: Vertical in the sense that cable areas do not overlap and hence, different franchise areas do not compete with each other. See for example the ntl/Telewest merger.

Endnote 36: The question of how and to what extent sustainability benefits need to be ‘shared’ with consumers is discussed in the CMA’s recent advice to government on sustainability in the competition and consumer law regime.

Endnote 37: Sparrow, M. ‘The Regulatory Craft’