Written by

Written by

Tom Slater

Senior Buildings Sustainability Consultant

Arup

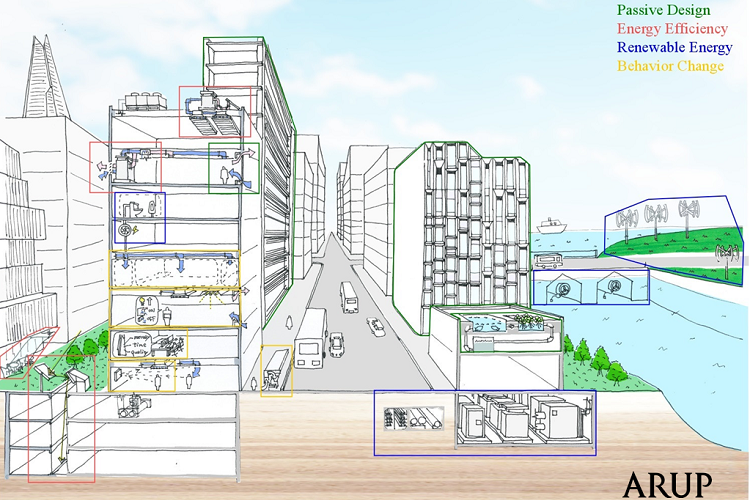

With the built environment responsible for an estimated 38% of Welsh carbon emissions, decarbonisation through expansion of low carbon energy generation, and reduction in demand via zero-carbon design, are key priorities and a fundamental response to the climate emergency.

In many ways, Wales is in a strong position in its approach to decarbonisation. As well as being rich in natural resources that can be used to reduce our carbon footprint, such as offshore wind, we have a government that has demonstrated a commitment to change through legislation such as in the Environmental (Wales) Act 2016 and the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (FGA) and committing to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

However, we need to acknowledge the barriers to decarbonisation, and particularly net zero carbon in buildings. With many decarbonisation commitments working to the same 30-year timeframe, there is a risk of putting off radical change, which will put more pressure on projects down the line, relying on future innovations that may or may not materialise, to keep us on track. So, what steps do we need to take now given that the immediate adoption of full scale zero-carbon solutions currently struggles to be commercially viable in Wales?

We need to recognise that the buildings we are designing and building today will still be contributing to Welsh carbon emissions in 30 years’ time. By not considering carbon at the beginning of a project, we miss a significant opportunity to reduce the impact of that building, whether through the embodied carbon associated with the structure, or the operational carbon associated with building services such as heating and cooling.

Environmental assessments have been the benchmark for planning, but despite moves to push industry best practice, this has not promoted strong environmental design or stimulated decarbonisation. BREEAM alone is not enough.

Instead, we need to consider wider aspects of sustainable development such as encouraging passive principles in early design stages, consideration of whole-life carbon and increasing the use of decarbonised energy sources. While the current Part L Regulations are outdated, the new domestic Part L Regulations are under consultation and should align with decarbonisation aims.

Another gap exists between the theoretical measure of a building’s sustainability, and its performance in operation. There is much evidence to suggest that buildings do not perform as well when completed as was anticipated when they were being designed – a difference known as the performance gap. Display Energy Certificates (DECs) report on actual measured energy consumption in completed buildings, which will help to close this gap while informing owners and operators how their assets are used, and when building improvements are likely to be needed.

Despite the challenges, moving to low-carbon design brings opportunities for engagement and collaboration, and that is where my greatest hope lies. We’re seeing major companies wanting change, and by working closely together we can help to steer better design and innovation.

On a personal level, watching Sir David Attenborough’s Extinction and A Life on our Planet hits home and adds impetus to my desire to pursue excellence in my work. Those of us with a passion for the net zero carbon agenda need to educate and influence our clients, colleagues and collaborators. Whether it’s embracing opportunities with clients, developing technical innovations or sharing best practice with others in the industry, we must make sure that we are making and encouraging other to make the bold decisions that must be taken now if we are to meet our net zero commitments and contribute to a sustainable future.